Table of Contents

We are a translation and localisation agency. We make mistakes. Or rather, we make some kinds of mistakes. No one is perfect.

The important thing is to learn from your mistakes, as so many people say, but most importantly, we add, to understand what kinds of mistakes are acceptable and what kinds are not.

We feel like it’s not very clear to the public what the real challenges and risks of localisation are. Sure, you can completely mistranslate a word or an entire sentence. Depending on the text and the context, this can have detrimental economic and operational consequences for the translation client, who will normally want to blame the translator.

These things are part of the translator’s life. Running into such an error has happened to everybody at least once. Just as every doctor has had to lose a patient or every singer has had to hit the wrong note in a concert. This type of errors is also the easiest to detect by any reader or user, so when we talk about translation errors we mean nothing more than that, an occasional mistake.

As problematic as they are, these mistakes are things that rarely happen, at most a handful of times in a translator’s career. We prepare specifically to avoid them.

What many users don’t realise is the importance of many other facets of the activity of localisation, aspects that are perhaps less obvious but, precisely because of that more deceptive, that often are not identified until long after the communication has taken place.

They range from erroneous or crude cultural references, to translations that are correct in themselves but leave room for ambiguity, to the age-old question of local adaptation of expressively charged messages, whether irony, humour or emotion.

A sore point is that, alas, translators themselves often underestimate the importance of these aspects and abuse “technicalities”, losing sight of these equally important issues.

We will never be able to avoid all mistakes. But we can avoid the right ones.

Note: you may have already heard of some of the known errors mentioned in this article. Please note: some are real hoaxes, and we’ll tell you which.

Have you ever driven a...?

For some reason when it comes to mistranslated product names or, worse, not translated at all with disastrous consequences, the first examples that come to mind are car models.

Real cases...

The leader (at least here in Spain...) is surely the case of the Mitsubishi Pajero, a model of the Japanese manufacturer launched in 1982 “under a unified name”, that is, keeping, at least at first, the same name for all markets. Too bad that “Pajero” has, in most Spanish parlances, a much more common meaning than that designating a South American feline, the Pampas cat or precisely Leopardus pajeros.

Instead, the most common meaning refers to masturbation, a factor that led company executives to change the name to Mitsubishi Montero shortly after launch. Lest there be any disbelief or exaggeration, there has been no evidence to date of a negative impact on auto sales in Spanish-speaking countries.

However, if the name was immediately changed as a result of the popularity of the misunderstanding, it is clear that the decision makers within Mitsubishi preferred not to take the risk of this potential negative effect on the business.

Not to mention that, if for a giant like the Japanese car manufacturer the image risk was just around the corner, for a growing or less solid company such an oversight can prove fatal.

The same is true for the Honda Jazz. Few people know that this name is not the original name of the car. As reported by R. G. Capuano in his 111 translation mistakes that changed the world, for the launch in European markets the company had thought of Honda Fitta, a slight adaptation of the name for Asia and the US Honda Fit.

If for an Italian the term “fitta” for a car can provoke a smile, we dare not imagine the reaction that would have had a Swedish consumer, where the word “fitta” designates in a not necessarily elegant way the female genitals.

The decision to change the name was taken at the last moment, and it is reported that the advertising campaign had already been organized with the slogan “Honda Fitta. Small on the outside, big on the inside.” which would have only added layers of awkwardness if the problem wasn’t identified in time.

...and urban legends.

A different matter, instead, for two metropolitan legends that circulate around the most popular Italian manufacturer, FIAT. There have been rumours for some time that the company has had problems with the international launch of its Ritmo and Marea models.

If in the first case the name change took place, referring in particular to the U.S. market, this was almost certainly not due to the association that, according to some, the name Ritmo might have with a brand of condoms. In the case of Marea and its reference to nausea, mareo, in Spanish-speaking countries, there was in practice neither a change of name nor a drop in sales relative to expectations.

Why do we like them so much?

Real or not, what we want to point out is that the emphasis placed almost obsessively on cases like these by those who want to give a polish to the translator’s badge demonstrates, in our opinion, a shyness if not an insecurity that has no reason to exist in the field of localisation.

Whoever works in the field of localisation, whether at the campaign management level or at the individual translation level, plays a central role in the international launch of any sales or communications initiative. An equally important role, in foreign markets, as that of the person who planned the campaign from the beginning, if we consider that the volume of adaptations required, is often such that the final product is hardly recognizable.

What we don’t have to do (and yes, we include ourselves) as localisers is getting lost in the cauldron of macro-errors by having to give authority to the activity we do.

Each of us thinks “I would have noticed if the car model we were about to launch was synonymous with ‘geek’ in another language...”, and it’s certainly true. However, if a multinational company like Mitsubishi lets it slip through their fingers, this is not due to a single mistake but, perhaps, to a structural flaw in the processes of campaign management and validation.

To better understand what we mean, let’s now look at other cases, inside and outside the strictly business world, where the issues raised by translation and adaptation are more subtle and, we believe, more worthy of attention.

Manhunt?

Year 2009, the film Slumdog Millionaire, 2008, by Danny Boyle wins Oscars and gains a great success with audiences in many international markets, including Italy. It is precisely in the edition dubbed in Italian, however, that there is a translation error in the dubbing whose connotations risk going far beyond the linguistic oversight.

Cultural differences: values and sensitivity

The film wants in fact also to denounce the dramatic situation of civil guerrilla war with a religious background that has not yet left many of the Indian states. One of the key scenes in the plot shows the protagonist’s mother, a Muslim like himself, killed by a group of Hindu extremists.

The translation error lies in the fact that the cry that starts the scene has been translated from “They are Muslims, get them” to the opposite meaning expression “They are Muslins, let’s run away”.

Now, regardless of the certainty of the mother’s death, this mistranslation generates doubts and in particular risks suggesting that the Muslims were the assailants, contrary to the common thread of the entire film.

This is exactly the point to pay attention to. While an error regarding a word or expression is in itself a hazard of the trade, what turns one’s nose up in this case is the inconsistency with the overall meaning of the film.

The work of study, analysis, and immersion in the context of what is being translated are constitutive activities of the work of localisation and translation, equal if not more important than any purely linguistic research.

In fact, if we are localising a message in a foreign language we need to pay attention to the literal meaning of the text as much as to the whole weave of symbolic meanings conveyed by elements such as tone of voice and style, and the system of cultural references embedded in the language in question.

Let’s take as an example another glaring case, that of the phone company Orange, a veritable giant in the industry that from its French base has expanded over time to a myriad of different countries and markets. The multinational company has been the victim of a slip in the past, in this case, we say, very difficult to avoid, since it involves the very name of the company.

When opening the Northern Ireland market, the combination of business name and slogan “The future’s bright. The future’s Orange (having the same meaning in both French and English).” was not well received because there the colour orange has long been a hallmark of the Protestant faction loyal to the United Kingdom, as opposed to the Catholic faction advocating separation from the British crown.

Cultural differences: images and symbols

A famous mistake with a much lower emotional charge but, in a certain sense, with a high “visual” charge is that of the company Paxam, an Iranian manufacturer of household items and consumer goods. At the launch of one of their detergents called “Barf” the company made a rather gross error that signals a dangerous level of carelessness, not only from a pure translation standpoint.

If “Barf” is the Persian word for “snow”, not only did the company decide not to translate the name, losing the evocative and almost poetic effect of the choice, but they also lost sight of the fact that in colloquial English “barf” means to vomit.

Finally, let’s take a look at two bad examples of localisation where, absurdly, the written word wasn’t even needed to give rise to misunderstandings and hurt business results.

Very famous is the misadventure of the Pampers company in Japan, a market that in itself often proves to be hostile for most foreign companies, due to very high quality standards and ubiquitous local competitors. Add to that an inattention to cultural differences, and it can take years of time and significant additional investment to recover from the debacle.

In the case of Pampers, the oversight was as innocent as the decision to place a stork carrying a baby on the ads, an image that in itself is very common for most markets considered Western. Unfortunately for the company, however, in Japan this cultural reference is meaningless and has actually caused confusion and bewilderment among consumers.

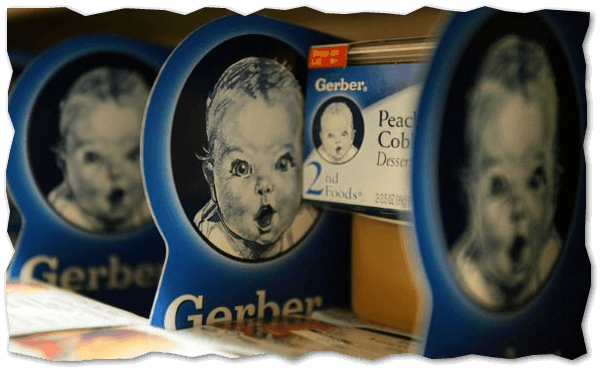

Less sensational, but still widely discussed, is the case of Gerber, a manufacturer of, among other things, baby food. When launching its product line in Ethiopia, the company made the macroscopic mistake of not changing the packaging and thus leaving the same images that the packaging featured in all other markets.

What they had not taken into account is that in Ethiopia, and various other Sub-Saharan African countries, the custom for food products is to have packaging where the picture instead represents the contents of the box. Food products, baby food...it’s easy to imagine how this story ended.

Conclusion

We have no data to support this statement, but personally, we believe that very few consumers in Ethiopia really thought that they were trying to sell them baby meat.

However, the doubt remains: what image will consumers have when they see the name of that company again? More importantly, were this and the other mistakes we mentioned before avoidable?

In our own small way, we don’t allow ourselves to take on that all-too-common pose in the corporate arena of “I, in their place, would have done so much better.” *This is almost never true.

On the contrary, we launch a warning to all companies that every day repeat the same mistakes and continue to waste time and money in the long term to save a handful of euros in the short term. Many companies fall into these localisation and translation traps because, in order to succeed in an international campaign, it is not enough to hit the bull’s eye in every single step. Instead, we need the whole process to work individually and as a whole, like a well-rehearsed orchestra.

At Qabiria we are translators, writers, technicians and creators (or “transcreators”, to use a term now fashionable). We have incorporated more and more expertise into the team, and we don’t plan to stop. In addition to our translation services, project management and business writing we offer language, technology and strategic consulting for internationalisation.

We started 13 years ago as a translation agency. We have become language partners in the round.

Like us, there are other companies worthy of all due respect, and if you’ve already found one, hang on to it. Otherwise, contact us. Tell us about your ambitions, your anxieties, your challenges. We’ll also help you take your message across borders, always in a precise and effective way and straight to the point.